The first helicopter was about to be born in Spain: this was the amazing “Spanish Dragonfly”

If the convulsive 20th century had not shaken Spain with a three-year fratricidal war, today the word helicopter might sound like technical jargon. Instead we would talk about “Spanish dragonflies”. Nor would the name tell us much. Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky, one of the “fathers” of modern rotorcraft. When asked about the key figures of the invention, we would respond with more traditional surnames: Cantero Villamil. Federico Cantero Villamil.

That perhaps, and only perhaps, if the war and its trail of misery had not gotten in the way.

Ucronías and other counterfactual stories aside, the truth is that Spain had the potential to become the cradle of modern helicopters and get ahead of Sikorsky. Juan de la Cierva provided the key technology and Stonemason Villamil got to start a prototype in the early 1930s.

He lost his ticket—or at least his chances in the race—because of the blow of the war; but that does not mean that he did not fight back and star in his own chapter in the history of aeronautics. From the first, De la Cierva, we began to vindicate his legacy years ago; the second is still unknown. So much so that he doesn’t have not even a street of his own in his native Madrid.

Who was Cantero Villamil?

And what was that about the “Spanish Dragonfly”?

the dream of flying

Patent No. 149788.

Every generation has its obsessions. Today we dream of stepping on Mars and exploring the lunar South Pole. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th they did it by flying, an idea that germinated in some of the most brilliant brains of Spain at the turn of the century. It happened to Leonardo Torres Quevedo. To Emilio Herrera Linares. To Juan de la Cierva. And Federico Cantero Villamil (1874-1946), perhaps the least known of all. Each one with its own peculiarities and approaches.

In the case of Cantero, the dream of flying through the skies caught on very soon, during his high school years. And while his footsteps wouldn’t exactly lead him into aeronautics—on paper he was a civil engineer—and he had to spend much of his time on hydroelectric projects and railwaymen, flying was an obsession that accompanied him until the end of his days.

The engineer from Madrid thoroughly studied the challenges of flight, read the works of Gustave Eiffel and even wrote to another Frenchman, the pilot Louis Bleriot, with the purpose of helping him in the design of his own airplane. His interest ended up focusing, however, on a peculiar way of flying through the skies, different from the ship that, for example, the wright brothers for his 1903 flights in the US: the helicopter. Advantages it certainly had: its vertical takeoff and landing promised to maneuver more safely and in smaller spaces.

By 1910 Cantero was already registering his first ideas about the device. He was not the first, and certainly not the only one, to work along similar lines. Outside of Da Vinci’s sketches from the 15th century, other minds were wondering how to improve the device. in 1907 Paul Cornu already had a peculiar double-rotor prototype and not long after Raul Pateras of Pescara it was already manufacturing more or less operative devices; in Spain itself Juan de la Cierva experimented with the autogyro and —most importantly— its rotors, so important that pioneers like the Sikorsky recognized their role.

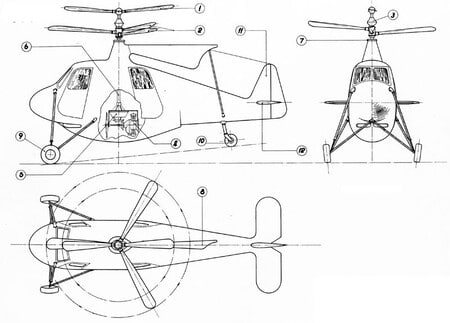

Viblandi II Dragonfly Prototype (1941).

In that race, Cantero Villamil devoted great efforts to solve the lift problem. He did not have enough means, so to carry out his own tests he built a home aerodynamics lab, a full-fledged test bench for rotors that he set up with more enthusiasm than resources in the garden of his own house, in Zamora. There he completed tests that he later documented in detail following the method proposed by Eiffel. Over the years he registered patents and came into contact with Herrera and the Cuatro Vientos testing laboratory.

By the mid-1930s his works were mature enough to decide to go a step further and create a prototype. The result is the “Viblandi Dragonfly”, a name that combines Cantero’s surname with that of the partners with whom he allied to manufacture it: the engineer Pedro Blanco and the mechanic Antonio Díaz. The brand liked the measures and it did not take long for it to be retouched to end up reduced to “Spanish Libélula”, a helicopter “made in Spain”.

The problem is that in the Spain of 1935 bad winds were blowing for projects like yours.

winds of war

Patent No. 89820

Overnight and by art of war, the inventor from Madrid found himself in an even more grotesque situation than the rotor tests he had been forced to carry out in the garden of his house in Zamora: how the handful of kilometers that separated him from his prototype and workshop became an insurmountable distance that hindered any progress possible.

When the war broke out, Cantero Villamil was in territory controlled by the rebels. His prototype of Libélula, in his workshop in Republican Madrid. as detailed The Independentthey even hid the different parts of the prototype and the engine in houses in the capital.

And so, what the complexity of the project or the scarcity of resources had not achieved, the war did: the “Libélula” chained a forced stoppage for three tragic years in which the Spanish aeronautics suffered two other losses: the death of De la Cierva and the exile of Herrera.

The war could put the brakes on in Spain, but not in other countries. In the middle of 1936, the Focke-Wulf firm managed to get its Focke-Wulf Fw 61 took flight and three years later, in the late summer of 1939, Sikorsky made history with the Vought-Sikorsky VS-300, an already fully viable aircraft. By 1942 he had a design that could even manufacture at industrial level and en masse.

Early model of Juan de la Cierva’s autogyro.

The pioneer train—or the flight, for that matter—had passed; but Cantero did not throw in the towel. He kept working on the design of it, polishing it, perfecting the details. In 1940 he managed patent no. 149788 for the “Libélula Viblandi” and three years later he finished a prototype that, the inventor speculated, could perhaps fly in low-altitude areas. Against him, however, he had an enemy almost greater than the straits of the 1920s or even the Civil War: postwar autarchy.

“I had the difficulty of materials, because just after the war there was no capacity to import,” explains Federico Cantero Núñezgrandson of the engineer, to The Spanish. Neither the time. In December 1946 tuberculosis ended his life and definitively settled the dream of the “Spanish Dragonfly”. Officially, his prototype never flew, although there are those who point out that it was tested under very controlled conditions that would include anchoring to the ground.

We have his photos, his memory.

And the uchronies about what could have happened if the war had not slipped into Cantero’s plans.

Images | Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (SPTO) Y Eulogia Merle – Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology

Reference-www.xataka.com